How Comic Journalism Changed the World

Hillary Chute teaches courses at the University of Chicago’s English Department with potentially life-changing topics such as “Pynchon/DeLillo and the Problem of America” and “The Aesthetics of Comics”. She’s into how we try to comprehend our understanding of culture and history in new ways, like through comic book journalism. She’ll present at the University of Hawaii tonight about how documentary comics have risen to become a “pathbreaking and sophisticated” method of reportage that “deserve attention and discussion,” she says. “I want to give a history to what I think has become the most powerful form of comics that we have today—how comics have emerged as nonfiction in the 21st Century, and how war has basically created this genre.”

Chute calls them “graphic narratives” because she says the graphic novel, “which is basically a publishing term invented in the ‘80s, doesn’t really describe the work that I study as fiction.”

It was established in the early 1970s when Art Spiegelman and Keiji Nakazawa published two separate books about World War Two from their respective viewpoints: Spiegelman’s 3-page “Maus” mixes factual evidence and his parent’s accounts of surviving Auschwitz with the author’s imagination and went on to become a more widely known graphic novel (also titled Maus), which won the Pulitzer in 1992 (the first graphic novel to do so); Nakazawa, however, writes from his perspective as a Japanese survivor of the Hiroshima bomb in 1945. Chute says these two “sort of opened the flood gates” to this type of storytelling.

Her most recent book, Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics, looks at the work of five writers/illustrators, including Marjane Satrapi, the author of the autobiographical Persepolis—artists who are undoubtedly affected by Spiegelman and Nakazawa’s works. Chute’s forthcoming book, Disaster is My Muse: Visual Witnessing, Comics, and Documentary Form, evaluates comics as documentary, how war was its catalyst, and how Spiegelman and Nakazawa have influenced the work of other prominent comic journalists such as Joe Sacco.

Wednesday through Friday, Chute will speak at various locations on the University of Hawaii’s Manoa campus about the graphic narrative form. Email [email protected] or call 956-3774 for more information. Tonight, she will discuss how cartoonists such as Spiegelman, Nakazawa, Sacco, and Satrapi have changed the landscape of visual and popular culture. These artists are sampled below, with notations by Chute.

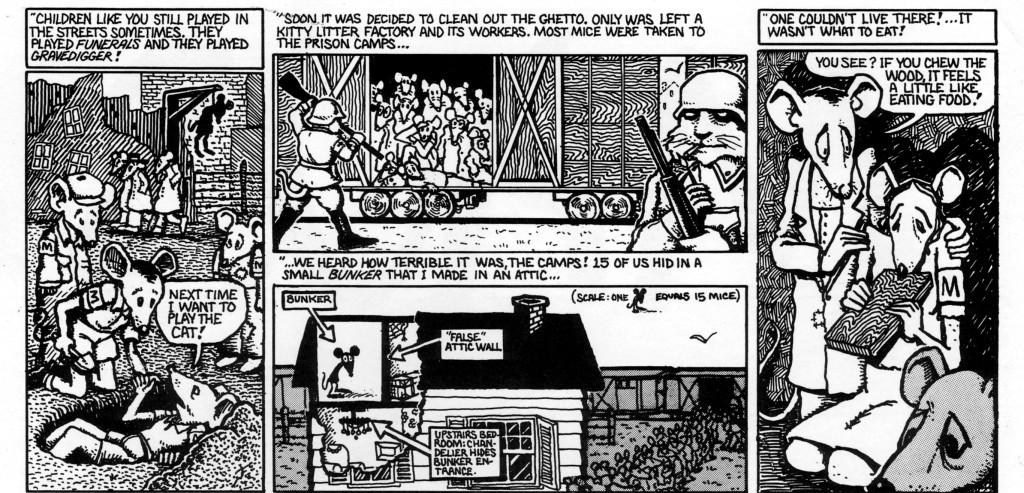

“This comes from Art Spiegelman’s 1972 3-page story, ‘Maus’, a lesser-known work than his Pulitzer-winning 1991 book, also titled Maus. Both of Art’s parents survived Auschwitz, and the quest of generations taking on what had happened to their parents led to this type of narrative. Art’s parents never discussed what happened to them, which is what a lot of second-generation kids grew up with—knowing about the war, but not understanding what was going on. Art was born in ’48. In the ’70s we see people whose lives were shaped by the war doing investigations into their family’s experience.

“One of the things I find really interesting about this part of the page is that you can see that his father’s testimony shapes what the cartoonist is drawing. At the top you have quotation marks, which is his father describing his experience in Auschwitz. What’s so interesting about this piece, which might seem conventional to us now but wasn’t at the time, this traumatic testimony in comics form, is that there’s also a certain burden of accuracy. So I love that, throughout these panels, there’s this diagram that Art draws of how his father created a small bunker in his attic in which to hide during the war. He’s trying to draw something expressive while trying to illustrate how he survived.

“Nakasawa, who himself survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki when he was six, was the author of the first so-called atomic bomb manga, I Saw It. Manga was already popular in Japan, but there was taboo around discussing the war and about being a victim of the bomb. So over time, for the children who grew up reckoning with their own personal experience, the urgency around expressing what war had been like, had a chance to metabolize. What you get in the ’70s is a sort of period in which these dormant feelings had a chance to be expressed by people who are now adults and can address their experiences.

“This subject of the atomic bomb was under-discussed, to put it lightly. People were stigmatized for talking about suffering, for coming out as atomic bomb survivors, so the fact that he decided to use the comic form to express something that couldn’t only be expressed in words is incredibly powerful. We get this in the silent panels in the page, too, through the first-person narrative. At the top of the page, we get these very expressionistic, almost abstract images that try to get at what it felt like experientially for him.

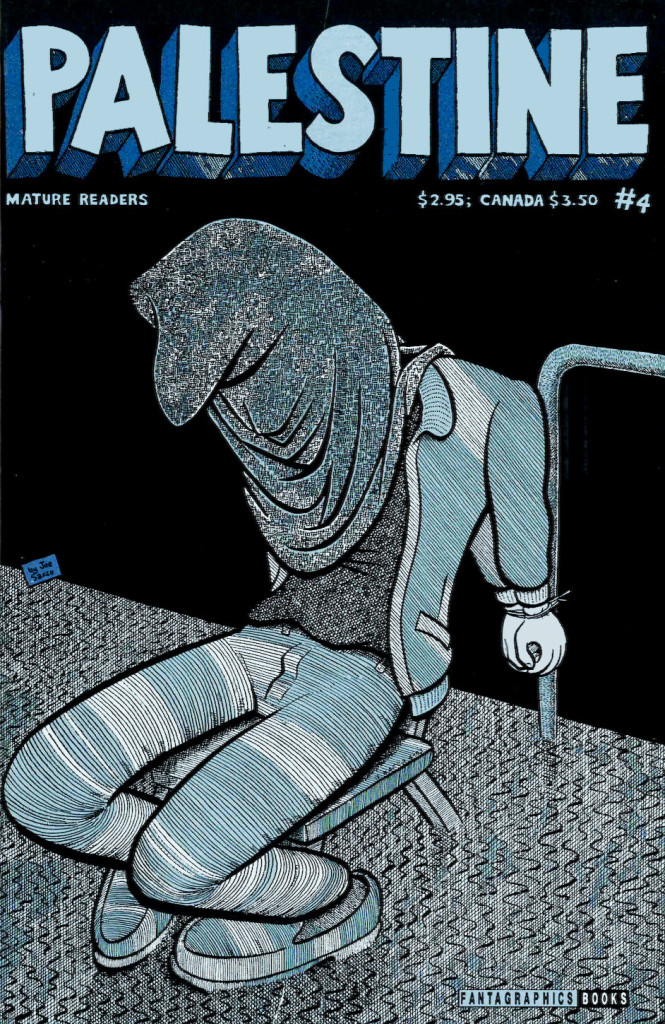

“Joe Sacco is an innovator in contemporary comics journalism, which he started with Palestine, and won the American Book Award. It got a lot of validation for this genre.

“This image has always seemed incredibly powerful to me. One of the things Joe does that’s similar to Spiegelman is solicit testimony. It’s both about research and oral history, and eliciting and being an interlocutor to people who have been traumatized, but it’s also about the kind of ethical leap Joe takes. He’s trying to imagine and visualize what in some cases is a very difficult situation for people. He’s motivated by the testimony of others and then he draws the testimony. Drawing the testimony of a Palestinian man being tortured in prison. Joe was trying to imagine what that’s like for a person who was hooded and tied to a chair.

“Joe interviewed about 100 people on both sides when he went to the Middle East in the early ’90s. It’s the context that makes it journalism, as he calls it, versus what Spiegelman is doing. By using big blue letters, ‘Palestine’, in a kind of powerful but almost awkward way, Joe takes this from something that so often has been used as recreation and diversion; he plays on comic book conventions explicitly, to do something serious.

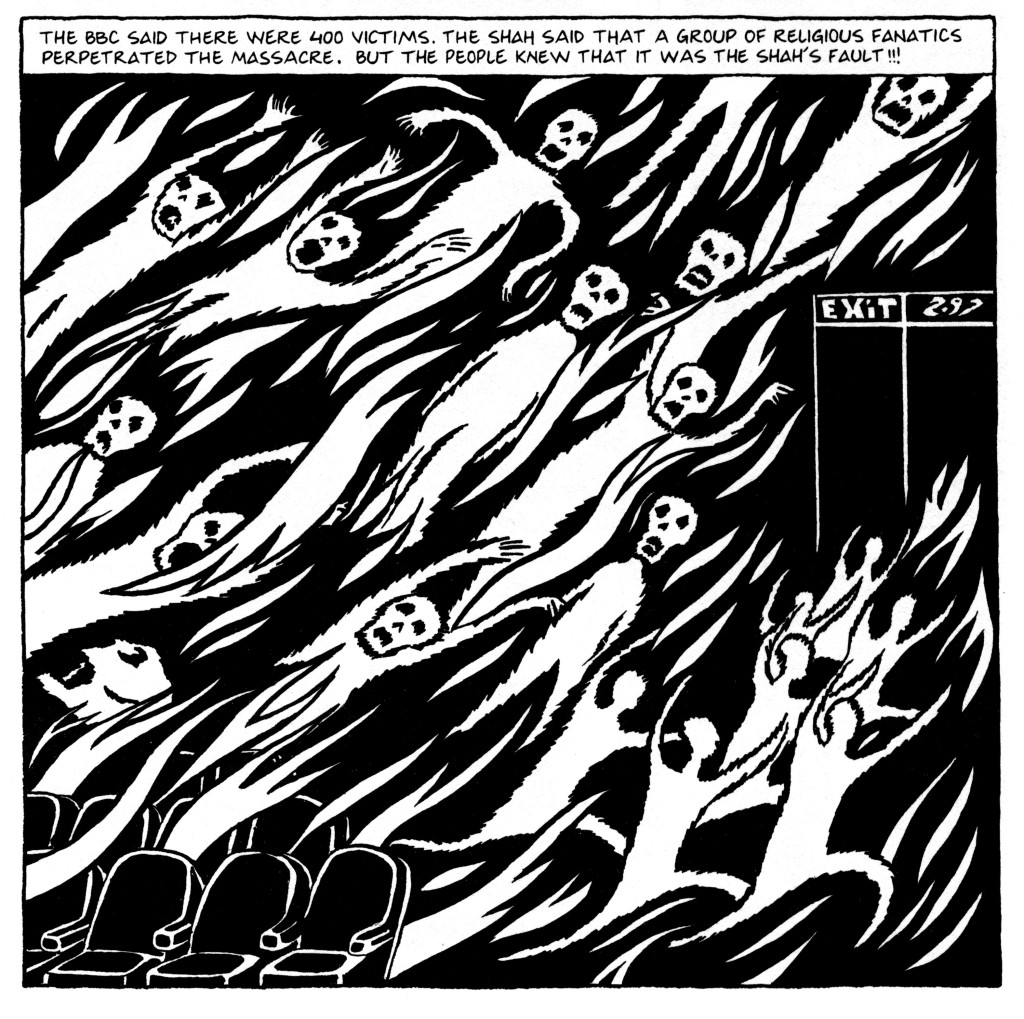

“Marjane Satrapi is influenced by both Spiegelman and Sacco, connecting with the question of style and the idea of witnessing in comics form. What’s so evocative to me about this image from Persepolis, an autobiographical narrative about Satrapi’s childhood and adult years in Iran’s Islamic revolution, is that it’s clearly not an image that is seen with the author’s own eyes. These people being murdered by being locked into a burning movie theater are pictured as ghosts. The image is reflecting the position of the protagonist—the child—when she hears about it on the radio. It’s an interesting kind of witnessing. It’s not exactly reporting, not exactly the faithful materialization of testimony as in ‘Maus’, but the effect that’s powerful is this idea of how a child would imagine all of these people being killed in a space that she knows. Persepolis does something interesting in the form of witnessing.”